By : RACHNA TYAGI

MUMBAI :

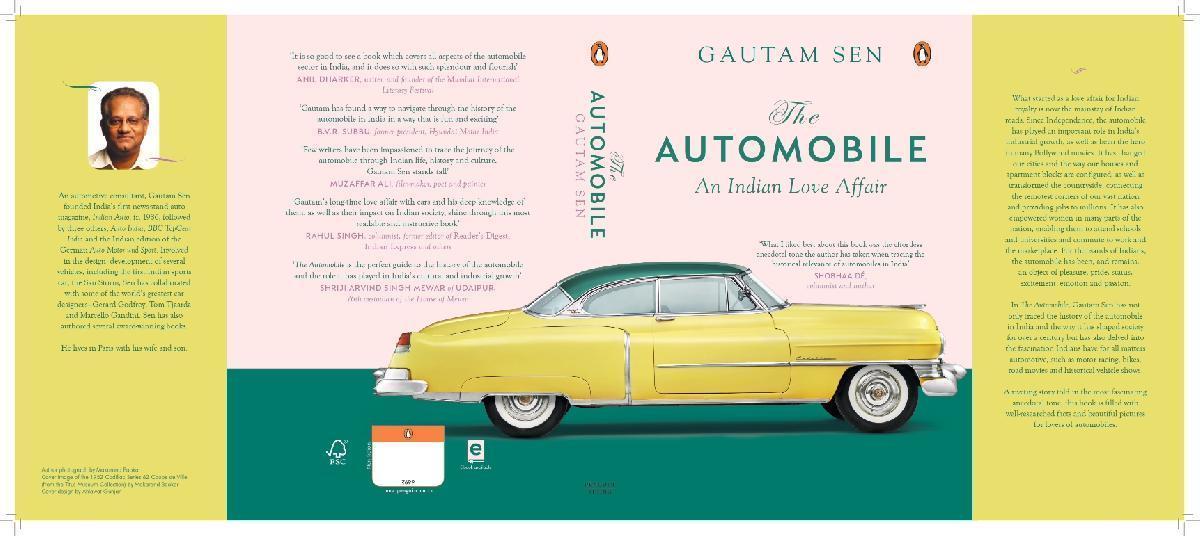

There is little doubt that author Gautam Sen’s new book, THE AUTOMOBILE: An Indian Love Affair, will go on to become the definitive ‘go to’ book for all those who want to satiate their thirst for knowledge about Indian car culture and history. In this interview he discusses all of that and more.

TOS: You have written several award-winning books over the years, and now, your latest book, THE AUTOMOBILE: An Indian Love Affair, brings readers up to speed with the Indian auto scene, capturing both, the past and the present. What prompted you to write this very important book for our times?

SEN: My earlier books on the Indian historic vehicle scene were more serious deep dives into specific cars and collectors, as well as the Indian princes, and the history of the automobile, specifically the industry, in India. They were addressed to the extremely serious enthusiasts and industry experts. I had always wanted to do a book for a more general audience, people who had more than a passing interest in automobiles, but ones who were not into specifications, technicalities, or intricate anorak facts. I also wanted to examine and understand better the social and cultural impact of the automobile in India and on Indians. With my literary agent Kanishka Gupta and Penguin that became possible.

TOS: For this book, which is extremely well researched, you have not only interacted with the royal families who have acquired these magnificent cars, added them to their priced collections, and are taking very good care of them, over generations, but you have also written about new age entrepreneurs who have been audacious enough to build fast cars in India. What has been the takeaway for you after interacting with these two dramatically different kinds of people?

SEN: The passion and enthusiasm for the automobile, whether it was with the princes or with the new age entrepreneurs, have been mostly similar. To some the automobile is a status symbol, a reflection of who they are and what they have achieved in life; to many others these objects of desire are cultural and design artefacts, ones which provide pleasure in terms of driving, aesthetics, liberty and mobility, and a memory of the good ole days. I do not see much difference between the enthusiasm of a maharaja and a current day industrialist. The real difference is between the wealthier collectors and the middle-class ones: the difference between those who acquire because they have the money power to do so, versus those who acquire because they really and truly love their vehicles and are willing to sacrifice other comforts to be able to have what they desperately would like to have and enjoy every bit of that ownership.

TOS: What were the challenges in writing this 'tome' considering the last year has been a frightfully difficult one for most people around the world...and the fact that you live in Paris and have written this book about the Indian auto scene...how difficult was it in terms of information gathering and actually putting pen to paper or clacking away at the keyboard, if you will, during these uncertain times?

SEN: I had completed writing this book in 2019. During 2018-2019 I had visited India several times, and spent months in India, and I had had the occasion to meet many of the people who figure in the book. A lot of the research though goes back to many years earlier, even decades, and I have referred extensively to my older notes too. Last year, in 2020, after the book was extremely well edited by Penguin’s Aparna Kumar, I did get back to many of the people in India, to check and update some of the facts, figures and information, and for those updates, I resorted to the phone, email and a few Zoom sessions. I must confess that most of 2020 was used to clack away at the keyboard for a couple of other book projects.

TOS: Besides the four wheelers, you have written extensively about the two-wheeler landscape in India as well. What did you enjoy writing about more? Why?

SEN: I have always had an abiding interest in two-wheelers, and over the years, especially when I was living in India, I owned a series of motorcycles (and a scooter). Also, to feed my other passion, which is design, the earliest projects I managed to work on were the designs of two-wheelers, a series of motorcycles for Enfield, Hero and Ideal Jawa. As cars are somehow more glamorous – and publishers prefer to underwrite books on cars – I have, until now, done books on cars. I was very happy to be able to “sneak in” a chapter on two-wheelers in this book, as this segment’s impact on India is immeasurable: If the Ford Model T, the VW Beetle and the Citroën 2CV changed the West, the Vespa/Bajaj 150, the Kinetic Luna and the Hero Honda CD100 changed India much more so than the Maruti 800 or the Ambassador.

TOS: Your book is packed with really juicy anecdotes, like the old lady who wanted her Rolls Royce to be between other Rolls Royces and on a marble floor and asked Pranlal Bhogilal to take away hers. If you had to pick a favourite one, which one would it be?

SEN: That is a difficult one! But perhaps the craziest one is the story of the Swan Car – the madness of the idea, the complexity (for its time) of the technology that went into having those special effects, the timelessness of the concept and the fact that there was another crazy guy who not only acquired that car (which had been banned from Calcutta), but also went on to take the trouble of making a “sibling” in the form of the Cygnet! It is stories like these that make the automobile such an important aspect of India’s cultural and industrial heritage.

TOS: As somebody with an astute observation when it came to various things about the Indian Auto industry and with all that you see around in Europe, combined with the fact that India is on its way to becoming the third largest auto market in the world, what would you say, are the top three trends that automakers will be leaning towards in a big way which we will be seeing in India in the coming months? Your thoughts...

SEN: Making cleaner and more sensible vehicles – that I believe is the most important trend, important not only in terms of ranking, but for the sake of society and the health of the future generations. The second will be beginnings of niche products, as until now, most manufacturers have concentrated on staying mainstream with mass volume products, whereas the profits are in the niches. The third is that of aligning increasingly with international norms and regulations, as well as (hopefully) setting benchmarks in terms of quality and expectations.

TOS: What can your readers look forward to next?

SEN: The books that I am currently working on are not India-specific. One, on the legendary designer, Tom Tjaarda, will be out next month, and the others will take a few more months. I hope to come back to an India-related book project later this year, but then it may take a few more years before it is out.

Sen and the Art of Motoring

Read an extract from chapter 4 of Gautam Sen's book, THE AUTOMOBILE: An Indian Love Affair, titled, A Car for the People:

Liberalization and the rest

After the famous economic ‘liberalization’ of 1991, international car majors began looking at India seriously and PSA Peugeot Citroën was the first to enter into an (ill-fated) joint venture with Premier Automobiles. South Korean carmaker Daewoo followed, inking a joint venture agreement with DCM, taking over from Toyota, DCM’s erstwhile partner in manufacturing light trucks. General Motors tied up with Hindustan Motors and Honda entered into a tie-up with Shriram Industrial Enterprises Ltd.

It was not until 1998-99 though that Maruti saw serious competition in the form of the Santro from the other South Korean carmaker, Hyundai Motors India Limited, the Matiz from Daewoo and, later, the indigenously developed Indica from Tata Motors. The coming competition though seemed to have caused a drop in Maruti Udyog’s sales from 327,240 to 309,544 for 1997-98, which until then had been going from strength to strength. By 1996-97, Maruti’s market share had risen to an impressive 79.6 per cent of India’s passenger car market; in the financial year 1997-98, Maruti’s market share was a staggering 82.7 per cent.

Interestingly enough, clones of the Maruti 800 were also produced in other parts of the world, including the country across the border. The Suzuki SB308 was sold in Pakistan as the Mehran. Across the other border, in China, the SB308 was produced by several Chinese carmakers, with badges reading (in Mandarin!): Chang’an SC 7080, Jiangbei Alto JJ 7080, Jiangnan JNJ 7080 Alto, or Xian Alto QCJ 7080. When Zotye took over Jiangnan, the car was badged a Zotye JN Auto. A version of the JN Auto was also assembled in Tunisia for the African markets until 2005, and to confuse the issue further, was badged a Peugeot JN Mini!

What was to Japan an interim fifth generation model (with a planned obsolescence of five years) of a line that was into its 14th generation by 2020, it became the people’s car for not just India, but also, to an extent, Pakistan and China. Amusingly enough, the 800 was never intended by its designers to be a people’s car—it was just another competitively priced kei-jidosha car, one, which was meeting a Japanese-specific market requirement, but thanks to the strange twists of fate, it became the car, which put the world’s second most populated nation on wheels.

This begets the question: could any other similar car with similar pricing and specifications as well have become India’s first people’s car? R C Bhargava expressed his doubts to the author: 'It’s not just a question of the right product. The right partner and people involved are no less important. ' Bhargava has always maintained that Osamu Suzuki and the senior management at Suzuki Motors were no less crucial in the success story of Maruti Udyog and the Maruti 800.

Of course, detractors will point out that the success story of the Maruti 800 and Maruti Udyog, the carmaker, had very little to do with the collaborator or Mr Suzuki, but more to do with the clear mandate from the Government of India that this project had to succeed at any cost. 'Every rule of the book that could be bent to make the project work was bent . . . every rule-bending resorted to, ' said an industry veteran—who wishes to remain anonymous—to this author.

‘To start with, licence was given to just one other insignificant carmaker, Sipani Automobiles,’ says that industry veteran, ‘then import duties were reduced drastically, as was excise. Almost complete cars were allowed to be imported initially. Maruti was always behind on its localization commitments, yet the government turned a blind eye to that. Lower excise for fuel-efficient vehicles was just an excuse to justify minimal taxation. And then when Rajiv Gandhi came to power and decided to “broadband” licensing, which was supposed to allow other four-wheeler manufacturers to make cars too, their joint venture proposals were never given a green signal, so that Maruti could be continuously protected. After all that if you cannot succeed, then you need to be incredibly incompetent!’

Krishnamurthy concurs, mentioning to the author, ‘Yes, any other similarly priced small car from Japan would have succeeded for sure. Of course, working with Suzuki was easier as versus giants like Mitsubishi, but the initial success of the Maruti 800 and Maruti Udyog is mainly thanks to the Indian management.’

Yet, there is no denying that Maruti Udyog was a favoured child and the Maruti 800 had a charmed early life. Maitreya Doshi, the managing director of Premier Limited, pointed out to the author that the government largesse in terms of tax and excise benefits gave Maruti ‘at the least a 15 per cent cost advantage over the others’. That was so for the first—crucial—decade of the company’s existence.

Existing carmakers such as Hindustan Motors, Premier Automobiles and Standard Motors, all had the opportunity to work out new collaboration deals to bring in cars and designs that could have competed with the 800. Yet they chose to bring in outdated designs with outmoded technology, launching cars like the Hindustan Contessa (based on a Vauxhall design from 1972), Premier 118NE (a Fiat design, via Fiat’s then Spanish subsidiary Seat, from 1966) and the Standard 2000 (a Rover from 1976, powered by an engine, which went back to the 1950s). Of these, the 118NE, at its launch, created quite a buzz, with some 1,08,000 cars booked and Rs 118 crore garnered by the carmaker, but quality issues saw the waiting list dwindling rapidly.

It was only by the mid to late 1990s, after the 'liberalisation ' of 1991, that Maruti Udyog had serious competition. Yet, not only did the 800 survive, it thrived despite a crowd of very worthy competitors launching several fine small cars, from the Fiat Uno to the Tata Indica.

When Premier Automobiles tied up with Fiat of Italy to announce the launch of the Fiat Uno, some 290,662 punters put down almost Rs 600 crore as booking deposit (creating a record, which remains unsurpassed). Everyone believed that the days of the Maruti 800 was numbered. Trade union militant Datta Samant though decided to 'intervene ' and history took a very different turn as Premier Automobiles’ two joint ventures—one with Fiat and the other with Peugeot—came apart, allowing the 800 to remain the king of the hill.

Tata’s Indica, Hyundai’s Santro and Daewoo’s Matiz also looked like serious threats when they were unveiled in early 1998. Alas, they priced themselves out of the 800’s segment. It was not until the 800’s intended successor, the Alto, came along (in September 2000) that the 800 finally had competition. Yet, it took the Alto another five long years to topple the 800, to begin a new chapter in India’s 'people’s car ' history.

*Extracted with permission from Penguin Random House India.